The ACalabash website is no longer available, so I’m storing my interview with Andy Caul, published in September 2021, here.

Tell me: Who is Celia Sorhaindo?

Well, that is a difficult question because I don’t know if we ever truly know who we are. We are always works in progress. I’ll start with the standard stuff. I was born in the small nature island of the Commonwealth of Dominica (often confused with the Dominican Republic). I lived here until I was eight years old and then my family and I migrated to England. I lived in England for quite some time, nearly 30 years, did my schooling there, worked there as a computer programmer, and then decided to move back. Ever since leaving Dominica, I dreamed about coming back home, but you know how it is when you go away for a long time – it’s always very difficult to make that move back. I finally managed to make it back in 2005 and I’ve been here ever since.

Why do you write?

I don’t think it was a conscious decision that I made to start writing; it was just a spilling over – of needing to articulate something. And I don’t even think I realized what it was I wanted to articulate, but I felt there was this need. I think one of the things was lack of time before. I’d been very busy, working hard all my adult life, and it wasn’t until we were building our home, that I suddenly found I had a lot of time for my mind to wander – because I was doing mundane jobs, like sanding and varnishing, things like that. I had a lot of time to just think, and these words just came and I didn’t even know where they were coming from. So that was how it started. That’s why I believe writing is so powerful – it can remove blockages that you didn’t even realize were there. Also, I have a twin sister and she was a performance poet. She was my first introduction to the power of poetry. I used to go and see her perform and, you know, I used to get the shivers, and that made me realize the power of the spoken word. At school too, I always loved poetry and English, as well as Maths. Now, I write because I enjoy it, I find it cathartic and it helps me to think things through. I love the creative aspect of poetry as well.

Do you remember your first poem?

Recently, I was looking through an old notebook from way back in England and saw this poem I had written called “Set in (Setting) Sun”. It’s questioning whether once you leave home, especially at such a young age, whether ‘you’ can ever really return – the ‘you’ now would have changed so much, ‘home’ will have changed and your relationship to home can never be the same. I believe that was my first poem. I probably wrote other poems for school but I can’t remember them. But that’s the one I recall that I wrote personally, not for an exercise or anything like that. But up until the last few years, I’ve probably only written a handful of poems. Being focused about writing poetry is a relatively new endeavour for me.

Set in Sun

Egg-shell memory of dark setting sun,

held deep within, held tight, held long.

With time things pass no time like now;

I mourn, I grieve, I weep and cry

for things I can’t

re-call:

The loss, the pain, the creeping cold

within my soul—can I go back

again?

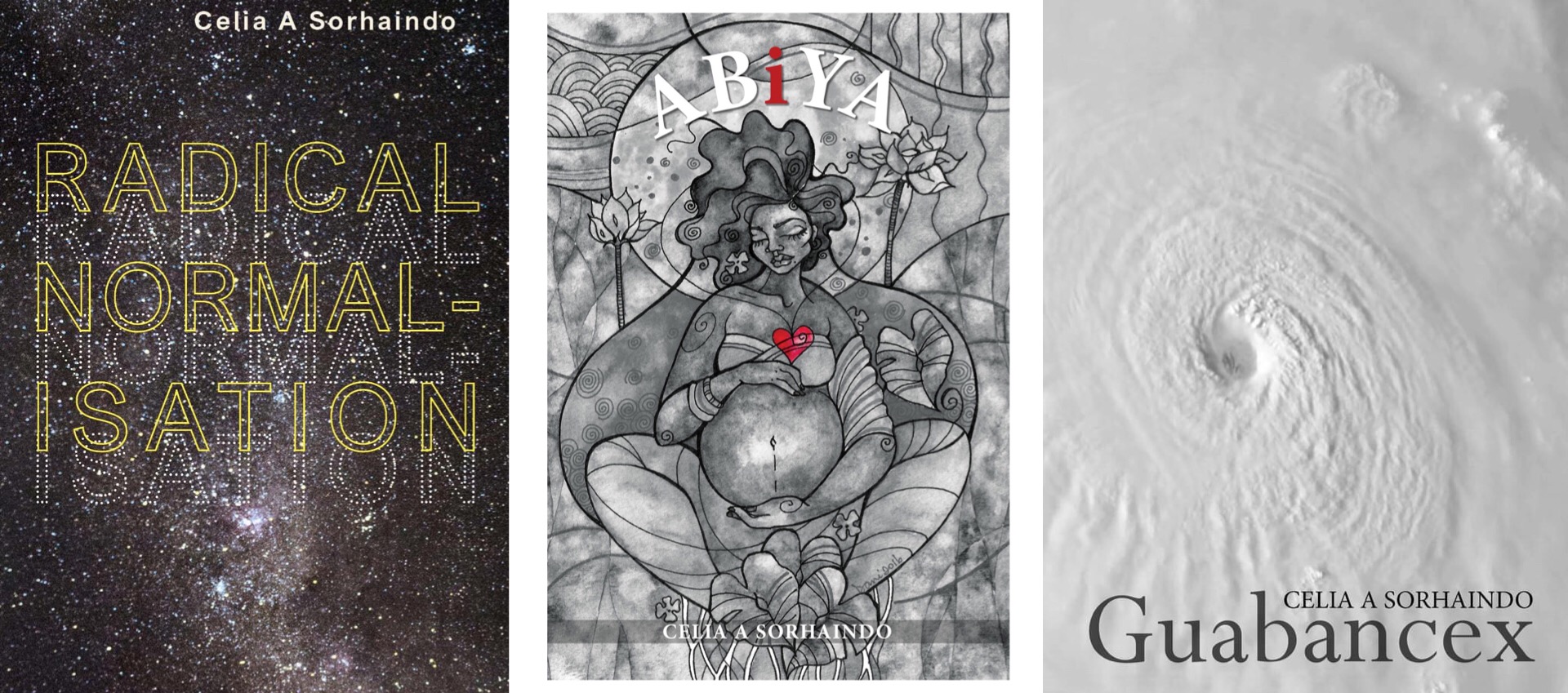

The title of the book, Guabancex, what’s the significance of the name?

The book is about hurricane Maria, the devastating category five hurricane that Dominica and other islands suffered back in 2017, and the name is a tribute to the memory of the indigenous people of the Caribbean: one of those groups were the Taino people and Guabancex was the name they gave to the supreme female spiritual entity associated with all natural destructive forces, including hurricanes. It means “one whose fury destroys everything”. But as well as the destructive side of Guabancex, she was also seen as the goddess of transformation, survival, renewal, and rebirth. The Taino lived higher up the island chain, more towards Dominican Republic, Cuba, Jamaica and not Dominica, but who knows, perhaps some Taino did live here at some point or perhaps some Dominicans carry Taino DNA. There is still so much we don’t know and will never fully know about the various people who lived in this region before colonization, but a common factor which appears across indigenous people, handed down and preserved in stories, songs and mythologies and some archaeological clues, is that they appear to have been keen observers of natural cycles, and seem to have had amazing knowledge about hurricanes, storms, and the seasons. On petroglyphs, they accurately depicted the swirling arms and eye of a hurricane before satellites, and they seemed to have had useful practical knowledge about where and how to build; knowledge about farming etc.; a respect for nature and trying to live in harmony with nature. So, for all these reasons I called the collection Guabancex.

The experience of Maria wasn’t just one story; it was an incredibly complicated time with lots of duality and polar opposite extremes of experience and emotions. Paradoxically, there was a lot of beauty, tenderness and love in the mix, not just trauma and horror. And for many people it meant having to start again. I thought that name captured everything that I was trying to put into the collection.

There’s a sense of lament, grief, reflection and mystery in Guabancex. Could you comment?

I think that is one of the reasons I write poetry: it helps me to think through problems and I’m always questioning things. But I don’t come to poetry necessarily to find nice clean resolutions either – there’s not always easy solutions to some of life’s problems or simple answers to some questions – but I try to investigate different points of view and different feelings. So yes, there is reflection, questioning, lamentation and grief in the collection, and many things remained unresolved and still a mystery to me at the end.

There was the question of why us again – why is it that the Caribbean, especially small island developing states, always seem to have to go through these trials? Why are we always in these vulnerable positions? We seem to have been enduring trials for so long. There was also the questioning of why other things happened that we did not expect. One of the frustrations during the whole period was some of the man-made problems. Why weren’t the utility companies and insurance companies more sympathetic to people’s situation? Why were there price hikes and other exploitations? Why did there appear to be uneven distribution of supplies? What were the underlying reasons why people looted? You know, trying to ask those difficult questions. Situations like the devastation of Maria, and what we’re going through now with the pandemic, can cause extreme behaviours and emotions. Fear can drive a lot of negative emotion; fear can also drive extreme reactions and panic, and traumatic situations often bring out the best and worst in people. So, it was a lot of questioning and trying to understand why this or that happened. And trying to find language to convey some of that complexity.

For example, the first poem of the collection, “a poem filled with words not metaphors,” is about this frustration of not being able to adequately articulate, or not even really wanting to articulate, the whole experience – words and language could never really hope do justice to the experience itself. The second one, “Hypotonic,” was trying to convey how water got into everything; how the force of water broke things down, broke us down, and how thinking about it can still make us “well up” – how the whole experience was not something we were going to get over easily or quickly; it takes time. When you go through trauma it’s not a simple linear path to healing; it’s constant ups and downs, and it can take a long time to get back to some kind of balance.

In the collection I also wanted to consider Maria as an entity, that Guabancex natural force – I actually don’t like the fact that hurricanes are named after people, especially when they cause so much death and destruction – so I personified hurricane Maria in one of the poems to work through some of that.

For me it was important not to convey a simplistic, stereotypical view of disaster or a voyeuristic performance of trauma and victimhood on the page. The period during and after Hurricane Maria was a complex time and, just as with human beings, it was deeply nuanced and not simply all bad or all good “character building”.

There were no answers or resolutions at the end, only the knowledge that we are survivors again, we have been survivors from day one and we are still trying to survive all now. If there was any resolution it would be that – the amazing capacity of the human spirit to survive.

In your last poem, “Hurricane PraXis (Xorcising Maria Xperience),” I see hope, resiliency, despair, and desperation. How do you read these as praxis?

I had read a few academic papers that focused on disasters. They had used the method of ‘praxis’ orientated research as an attempt to not just theorise or dehumanize, but I felt that they still seemed very detached from the people they were talking about; still using very academic language, clinical statistics and numbers – to me the connecting human element was often still missing. I also wondered if the people the researchers had engaged with, the subjects of the research, would ever get to see the research or understand the heavy academic language. So, my use of the word ‘Praxis’ was deliberate, to emphasise I didn’t want this creative depiction of the experiences to be just another abstract, disconnected, academic exercise. I wanted to show the complex, diverse and nuanced day to day human experiences of that time; that I had also lived through and been a part of – the complex mix of emotions which included hope, resiliency, despair, and desperation, and a whole range of other emotions – the human reality and not the theory, that hopefully everyone could identify with and ‘feel’, not just intellectualise about.

As I said, it’s not that every day was full of trauma and difficulty. There were moments of humour and of such beauty and love – you appreciated family, community, and you appreciated those little things that you never noticed because you were always so busy with your everyday life. And I also didn’t want this to be voyeuristic ‘disaster porn’ or a sanitised and romanticised version of a disaster experience; or a simplistic portrayal of us as helpless victims. In addition, I didn’t want the readers to remain detached observers, judging – I wanted to try and draw them in to be ‘in’ the emotions of the time, to be ‘with’ the experiences and emotions, and not just separated ‘witnesses’.

Many of us felt incredibly empowered during that time as well. Of course, I’m not saying that there wasn’t immense devastation and tragedy, but there was also a lot of human resilience. Also, we hear a lot that situations like hurricanes and disasters are levelling experiences, and although I agree to some extent, I remember reading this analogy that resonates – “we might be all going through the same storm, but we’re not all in the same boats.” And I think that’s an important point to consider – your capacity to protect yourself to a certain extent, mitigate against the impact – whether you lived in a concrete house or not, whether you were able to stock up with hurricane supplies, whether you had savings in your bank account, “who you knew” overseas or locally, whether you had another passport and could go and live somewhere else afterwards, whether your faith helped you get through, whether you already lived close to the land, already grew your own food, hunted, smoked your own meat, hand-washed your clothes, or had other useful life survival skills – all these were factors.

So, I think in the last poem, I saw the praxis as the reality, the fuller picture, looking at the details – an attempt at a truthful, honest recounting that we can perhaps learn from and that may help to better mitigate against the impact of future disasters. And the three big X’s in the title, the X that always marks the spot – the importance of love and compassion.

How does one exorcise the trauma of Maria?

I think this is an important question, Andy, because as Black people, African descendants – I believe there is such a thing as generational trauma that we inherit. And I don’t think that trauma and the impact of trauma on us as a people, has ever been fully recognized or acknowledged. I believe that some of this is what I was meaning about root causes of things like looting. It’s easy to just judge ‘those people’ as bad and label ‘them’ as such, without diving into the roots of why people acted the way they did – why ‘we’ acted the way we did. Why were some people able to cope better than others? I don’t think we’ve done that deep dive into trying to understand yet. But I do believe that some of that lies in the trauma embedded in our history.

I hope that as Caribbean people, we can one day recognize and address this issue of trauma, especially in terms of mental health. There’s such stigma and shame associated with mental health in the Caribbean, and I wish we could find some way of not stigmatizing or hiding it – a way in to talk openly about it, and deal with it with sensitivity, compassion and understanding.

So, for me, reading poetry and fiction and writing poetry, are cathartic and that’s one of my ways of dealing with traumatic experiences. You know, when you read work that totally resonates with your experience, or your thoughts and emotions, you feel that you’re not alone – that’s a reassuring and healing thing. And when you read through history, what our ancestors have survived, that is also empowering. Also, the act of creating something from words, that can hopefully move someone, connect with someone, or help someone to see or understand something in a different way, is extremely empowering.

My other healing rituals are backyard gardening and growing things I can eat; I love having my hands in the soil and walking on the ground. I love going for sea baths and hiking. I love watching the sun set – I’m totally addicted to clouds, you know, things like that. I’m very much a nature person and I find being in nature is incredibly spirit-nurturing and healing. Also spending quality time with family and making time and space for joy. But of course there’s also the traditional ways of speaking with a mental health professional or just speaking to somebody you trust and not holding it all inside – whatever works for you. I also think that any kind of artistic creation outlet is important for mental health, any kind of artistic self-expression, including dance, art, music, creative writing, craft etc. Also, physical exercise like running, walking and meditation, yoga etc – all those are things that can help you keep mentally balanced. Everybody’s process for “exorcising” trauma is different. I personally don’t think anyone should be forced into talking about a traumatic event if they are not ready, especially children. It’s important to respect people’s timelines for healing and respect that people heal at different rates and through different ways.

What is the connection between the form and the content of your poems?

For me, the form of poetry, including the traditional forms, and how the poem looks on the page, are important considerations when I write a poem, and can enhance the tension or increase the particular themes that I want to convey. The form of “Hypotonic” is very tight, regular and compact, and that was supposed to represent the idea of a container. In “Myrmecology,” which is about ants, I made it weave in and out to try and follow a trail, and the stanzas were eight lines each to represent the strict, formal regimen of ants and symbolically I felt 8 looked like an ant – so form is very important to me. In “Invoked” as well, the form represents the personification of the hurricane itself; the words at the beginning are all very scattered, representing the chaos of the hurricane, culminating in the chaotic screaming/shouting – capital letters – and then calming down into the normal text and the normal orderly lines. The same with “Hurricane PraXis (Xorcising Maria Xperience)”: the gaps in the form can represent lots of different things, gaps in time, gaps in memory, pauses. But also these instances of breaks in the text were breathing, release, points for readers. And, again, that was deliberate because although I wanted to show the relentlessness of the experience, I didn’t want readers to be totally overwhelmed. I used a lot of repetition as well, to represent that many days were spent thinking, saying, doing, repetitive things. For instance, you’ll see it interspersed throughout, “we are grateful to be alive”. So, form is very important to me: the form of the black words on the white page. I try to pay a lot of attention to that.

What advice would you give to aspiring poets?

I am quite wary about advice because I’m going through a process of reviewing a lot of what I was taught about poetry. I was taught poetry at school in England, and I’ve been to a few workshops more recently. At school, I can’t remember ever being asked if I enjoyed the poem we were studying or not, or how the poem made us feel emotionally. It was always more about literary analysis of the poem, what were the themes of the poem etc. We were also encouraged to do a lot of diving into the writer’s biography to try and figure out why the writer wrote this or that, which I think now is quite a dangerous thing because I’ve come to realize I was led to believe that the “I” in the poem was synonymous with the writer, when the “I” is usually a persona, a speaker, just as much another character. Of course, poems draw from personal experience, but you cannot assume that what you’re reading is factually true.

I also find sometimes there’s just too many rules for aspiring poets – so many do’s and don’ts, which I think can be quite stifling and perhaps harmful to creative growth. If somebody has taken the time and effort to create something heartfelt and sincere, who can judge, other than the writer, if it has the right to exist in the world or not, judge whether it’s worthy of the label poem or not, judge it good or bad? – there are all kinds of readers of poetry and there might be somebody in the world who will resonate with that poem, exactly the way it is written. Obviously, when it comes to submitting to journals and traditional publishers, there are particular requirements and aesthetics they may be specifically looking for – so that’s a whole different ‘game’.

If you’re just writing poetry because you want to write poetry, you enjoy writing poetry, my advice would be to do exactly as you please, do whatever you want, and have as much fun as possible – be as creative and daring as you can – there are no boundaries, there are no limits, only your imagination. So that would be my advice. There’s also the typical advice of read a lot as well. Personally, I enjoy doing that anyway. I love to read poetry and try to be diverse in my reading – but, again, don’t listen to anything I say – just do exactly as you please.

No Comments