The Kahini.org website is no longer available, so I’m storing my interview with Jordan Hartt published in June 2021, here.

Jordan Hartt: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with Kahini about your work! I’d love to start with “Guabanex,” your most recent book. How did it go from initial inspiration to published work?

Celia Sorhaindo: Dominica suffered a category five devastating hurricane in 2017, hurricane Maria, and it was a very traumatic time.

Lots of things happened—not only was the hurricane itself devastating, but what was also devastating in its own way, and what we didn’t expect, were the events after the hurricane, the difficulties we experienced, including manmade difficulties, like the telephone and insurance companies not being sympathetic, price hiking, looting, things like that.

Thankfully, my house stayed pretty much intact with mainly some flooding, but my mum, like the majority of people on the island, lost her roof. There was extensive damage to both inside and outside her home, it was a mess, so when the road was passable, I went to stay with her—she’s eighty-five and it was obviously a traumatic time for her.

So, after that period of literal day-to-day survival, trying to find water, trying to patch up the roof, salvaging what we could, clearing out, cleaning, trying to get the basics in order, I was left with all these complicated—sometimes paradoxical and conflicting—emotions and feelings.

I’ve loved poetry for many years, reading and listening to it. I’ve always found it a powerful and connecting literary form, but I was relatively new to writing it.

I had recently come back from a poetry writing workshop in the U.S., so poetry just seemed a good way of trying to work through some of that mental chaos and confusion.

At the time I wasn’t really thinking about a book and I was not coming to the poems seeking resolution or clear answers, I don’t think there are any—I was just using the form of poetry to try and work through my thoughts and feelings, trying not to be judgmental about what happened and trying to consider things from different points of view. For me it wasn’t a finger pointing “wrong” or “right” kind of experience, because I know, especially with things like looting, there are root causes, and I wanted to give space to investigate and think more deeply about some of those things—the nuances of human personality, community, politics, history, culture, environment, aid, dynamics of power, powerlessness and empowerment, poverty and wealth, living close to and away from the land, the concepts of strength, resilience and faith—all the issues bubbling under the surface that a devastating event can uncover.

I also knew that what gets portrayed on the news when a catastrophic event occurs, can be very different to the lived reality of the people going through the experience, so I wanted to record some of that in poetry.

Before the hurricane, I had sent Polly Pattullo—she’s a friend, and owner of Papillote Press publishing, and lives some of the time in Dominica—another older poetry manuscript of mine to look at, and sometime in 2019, we began discussing various publishing options. She suggested a shorter poetry pamphlet manuscript might be a better option for my first publication, and asked if I had anything. So that was the genesis.

I think I sent her the first few poems in July 2019, we signed the publishing contract in November and the copies were printed by December, so the process seemed pretty quick.

With regard to the title of the collection, I always pay attention to what’s in the space for me, what words are in the space, what do I keep seeing over and over again? And I had recently been coming across articles and videos about the indigenous Taíno people of the Caribbean region, and their female deity Guabancex, associated with all natural destructive forces, including hurricanes. She’s known as “one whose fury destroys everything,” but she’s not only the goddess of disaster, she’s also the goddess of rebirth and renewal.

Even though there is no evidence the Taíno reached as far as Dominica, it seemed an appropriate title for the book and a way of honoring the Taíno memory and the memory of all the indigenous people who perished due to colonization.

Also, we have an indigenous population here in Dominica called the Kalinago and people often aren’t aware of this.

So, I felt it important, especially considering what we are going through in terms of climate change and the knowledge indigenous peoples seem to have had about observing weather patterns, where to build your house, how to build your house—I think we can learn so much from their knowledge in these current times.

So, Papillote Press published Guabancex, and it was an amazing feeling: just over two years after the hurricane, to see something aesthetically beautiful, created from the debris and destruction.

I’ve mentioned this before elsewhere, holding the physical book in my hand, was life-affirming and as Kamau Brathwaite said, I too believe art can come out of catastrophe.

The book was published in February 2020, we had a book launch in Dominica, then pandemic hell broke lose all over the world, and that was, and is still, a whole other mix of weird and complicated emotions.

How do you go about promoting a book in this kind of environment, especially a book about a hurricane experience?

Although many of the themes relate to the resilience of the human spirit and how human beings can get through terrible situations, over time heal from terrible events, the importance of community, family, friends, and love, all those things. I hope readers see the “collateral beauty” side of Guabancex.

JH: It’s such a powerful meditation on the planet, on the increasing strength of the storms due to human-caused climate change. Were all the poems in it written post-hurricane?

CS: Yes, it was a few months after that I started dabbling, and I think at least six months after the hurricane before really being able to start writing again.

Although I kept a diary during that time, I didn’t consider writing poetry immediately afterwards. There was no headspace for writing, it was mentally and physically an exhausting time, and we were just concentrating on the day-to-day basics, food, water, rainproof shelter, etc.

But after a period, when those basic needs were covered and we could settle down a bit, the poetry writing really helped me then, helped me a lot.

I do recall though, that the experience made me even more committed that I would continue writing.

A month or so after Maria, I decided I would prove that commitment to myself. I sat in my vehicle one evening, outside one of maybe two or three places where you could get a wi-fi signal in our capital Roseau, in the muddy smelly chaos, and using my phone I submitted a few previously written poems to the UK’s national poetry competition.

I took it as a sign to carry on when one of them was long-listed.

JH: You were mentioning that you started as a poet by reading poetry as opposed to writing it. When did you first come to poetry as a child? What attracted you to the form, as a way of expression?

CS: Yeah, it’s interesting because I always loved English literature at school, although it was the usual old English writers at that time: Dickens, Shakespeare, Chaucer, George Eliot, etc., but I also loved maths.

We were kind of always told that you could only be good at one or the other and weren’t encouraged to explore both, but I’ve always loved both.

So, I went down more of a maths route. My career background in England was actually computer programming, that was my profession before I moved back to Dominica—very structured and ordered, not creative—but I also loved reading and played musical instruments.

I have a twin sister, Imani, and she was a performance poet. She was my first introduction to the power of poetry. When I used to go to hear her read, the hairs on my arms would stand up and that was how I learnt about the power of the spoken word, hearing writers recite or perform their poetry.

We also studied poetry at school in England and I enjoyed that as well. It was the standard English canon, Wordsworth, T. S. Eliot etc.—I never came across any Caribbean poetry at all during that time. It was after I moved back to Dominica in 2005 that I started exploring my creative side and came to re-experience my Island through creativity.

First of all, through using the camera and seeing the island through the camera lens. And then Alwin Bully—who is one of our cultural icons—he started the annual Nature Island Literary Festival. I think the first one was in 2008, and I was one of the organizing committee members. We had mostly Caribbean writers as guests, well known writers like Kwame Dawes, Colin Channer, Mervyn Morris, George Lamming, Oonya Kempadoo, Vladimir Lucien, Elizabeth Nunez, Kei Miller, Earl Lovelace, Derek Walcott etc., as well as our own local writers.

And that was my first introduction to Caribbean writers.

And the great thing was, because we’re such a small island—we are a population of less than 70,000 people and our literary circle is small—the sessions were often intimate sessions with not many people—we had these amazing writers come to Dominica and we could meet them and talk to them.

I don’t think I fully appreciated it at the time. Because I was new to the whole Caribbean literature scene, at the beginning I didn’t appreciate who these people were, but obviously that was a fantastic introduction for me and a huge inspiration.

That’s when I started reading Caribbean writers extensively, started getting to know and appreciate our rich Caribbean literary heritage.

Still at that time, it was more about reading and listening, I wasn’t thinking about writing poetry at all.

JH: So you were really coming to it as a listener, as a reader, as an audience member, as opposed to coming to it as a writer?

CS: Yeah, absolutely. That’s maybe one of the hang ups I have, because I don’t come from this literary background.

When you read a lot of the interviews with writers, especially American writers, they come from this long literary tradition—America has this recognized tradition of publishing, journals, workshops and MFA’s, things like that—and we in the Caribbean don’t necessarily have that and it has also not been my personal journey to writing.

We come from more of an oral literary tradition, more of an oral storytelling tradition, equally rich.

But saying that, considering our size and financial limitations, Dominicans seem to have had a vibrant writing community, since around the sixties and seventies, and have self-published quite a few books, relative to our population size.

Sometimes I find the literary world a bit daunting, because I don’t come from this MFA or literary academic background and I’m still not familiar with some of the terminology used. I’m still learning those terms and all the poetic craft tools.

Even now I get scared when I hear the word meter because I still don’t fully understand it! I don’t necessarily hear or recognize stress and unstressed syllables, or recognize formal rhythm, in the same way as others might, who have learned, been taught, to hear and understand these things. And meter is not something I consciously think about when I write.

When I read my poetry back to myself, I more go with what it feels and sounds like to me.

I read it over and over again, until nothing jars on my ears.

When I first started writing poetry, I would try and remember what I learned at school, and also go on the internet and read all these rules—poetry has to have alliteration, it has to have metaphors, you have to use similes etc—so writing my first poems, I’d have this checkbox list of all the things my poems needed in them, so that they would be “poetic.”

You can just imagine what kind of poems that I was writing!

I had checked all those boxes and I was very proud of my poems, but they seriously lacked any emotional depth and were missing a key ingredient which was “me” and my voice, or a voice that I was consciously in control of, because I was trying so hard to sound “poetic.”

It’s been a process of learning and unlearning, I think, especially as I was following what I had learned at school in England and I no longer agree with all that I was taught—how I was taught to write and read poetry—and from all accounts, because of our colonial history, I think it was taught the same way in the Caribbean.

We were taught to analyze poems, and I think that strange now, that I don’t recall ever being asked if we enjoyed the poem or asked how the poem made us feel!

It was more about investigating themes and reading the poet’s biography, to almost try to psychoanalyze the poem in terms of the poet’s life.

Now, I try not to see the speaker as the poet, to recognize that even when a poet uses the I, it doesn’t necessarily mean them, it’s always a persona and I try to observe more how the poem makes me feel.

Although I love the intellectual side of poetry, I wish we’d been taught to also appreciate and feel into the emotional side too, so yes, I think there’s been some unlearning in my writing journey.

JH: Would you talk a little bit about what I might call, quote-unquote, “Caribbean literature”? Poets I’ve talked with from Jamaica, Trinidad, St. Lucia, and other islands talk about the importance of the concepts of island and ocean, and how often it shows up in their work—how islands create separation, for instance, but also community. I’m not phrasing this well, but would you talk a little bit about your experience as a, again, quote-unquote, “Caribbean” writer?

CS: The complexities of labels are interesting: who decides the criteria of the label “Caribbean writer” and who or what literature is included, or excluded from that category?

I always say, it depends what the labels are used for, who is asking and why?

In the publishing industry, there always seems to be this need to categorize writers into this or that. I’m okay with being called a Caribbean writer, I am from the Caribbean and I write, and I’m a Dominican who writes too.

But I just wonder, from your point of view Jordan, when you hear the term Caribbean writer, what does it mean to you? What assumptions might you make about my writing?

For instance, because I didn’t grow up in the Caribbean—I grew up in England—a lot of my themes are about navigating this space of belonging and unbelonging, and some of my themes aren’t necessarily traditional Caribbean cultural themes.

Shivanee Ramlochan often says, “reading the Caribbean means you read the world.”

The Caribbean is such a mix of different people, different history, cultures, traditions, religions, literatures, languages—different stories. I also think of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s talk on “the danger of a single story”, and the danger of stereotypes.

In terms of your point about concepts and influences, coming from and living on an island, Dominica is often referred to as a “small Island”—you may have heard of Andrea Levy’s book “Small Island”—and there are many aspects to that too, and the term means different things in a Caribbean context than in an American context.

Living here, with the Caribbean Sea on one side and the Atlantic Ocean on the other, means the sea is now a significant presence in my life, I see it every day when I look outside, and ‘sea baths’ and sunsets are regular relaxation rituals. It’s interesting that Great Britain is also an island, part of the British Isles, and even though I lived relatively close to the coast in England, the sea was not a big part of my world, like it is now in Dominica.

Concepts of island and ocean, water in general, memory, the individual versus the collective, and my thoughts around these, would be a whole essay by itself. Before even coming across Derek Walcott’s poem “The Sea is History”, Kamau Brathwaite’s poem “Islands”, Richard Georges poetry collection, “Make Us All Islands”, and many others, I have been very much interested in themes around water holding memory and also what lies physically buried in the Atlantic Ocean, that we need to remember. Just the other week, seasonal Saharan dust was affecting us, and it’s a constant reminder to me that things are far more connected across great distances than we may fully realize. I also think about how the Kalinago and other indigenous tribes were awesome seafarers, and used the sea more like a river—they appear to have moved from island to island very easily and perhaps viewed them as less separate than we do now.

Writing and publishing while living in this region, generally speaking, there are issues with regard to access to things like workshops, financial support, physical book distribution, networks, and visibility.

You might need to work harder for your published work to be seen and read in the U.S. and U.K., even in other Caribbean islands—although the internet is definitely changing this.

There are also considerations of anonymity and self-censorship that might get played out differently in a country with a tiny population. There are advantages and disadvantages—for me the Caribbean writing community has been so welcoming and because it’s a relatively small space compared to Europe or America, I feel it has a familial feel.

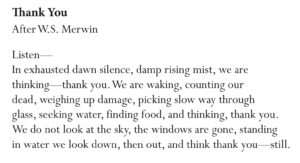

JH: in the book, the opening poem, “Hypotonic,” is shaped so differently than the others: would you talk about that poem?

CS: One of the things I love about poetry, written poetry, is what you can do with white space, with visual and poetic form, negative space, line breaks—the look of words on the page. Line breaks, form and wordplay are areas that I love to play with and I think the way the poem looks on the page, can enhance the themes and the tensions that you’re trying to explore.

With “Hypotonic,” some of what I was trying to portray was the power of water, destructive and constructive, how water managed to penetrate the most tightly sealed containers—we saw water inside sealed pill containers, inside lamps and water forced its way through tiny cracks in walls—how it got into the most unbelievable places and affected almost everything, breaking into things and breaking things down—one of these “closed-up vessels” being the speaker themselves. And even after lots of crying, which was another flow of water but this time a necessary healing release, they still find themselves welling up and the watery tears threaten to overflow again.

But there’s a tension in that the form of the poem on the page is very ordered, tight and compact, still sealed and contained. Also, the visual impact of the poem being surrounded by all the white space. There are so many other ways to interpret the look of the poem on the page and what it might mean to the reader. So, I’m playing with tensions between control and loss of control, internal and external, literal and metaphorical. Even though we were powerless in the face of the hurricane and all the havoc and destruction caused, one of the pleasures of poetry for me, is that you have such power to create from that debris, you can exercise so much control on the page—and one of those ways you can enact that control is through your use of visual and poetic form.

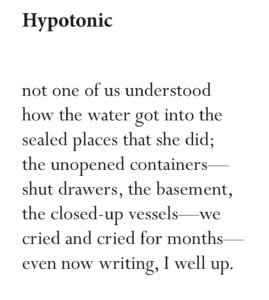

Again, in all the poems, the visual aesthetic plays a key role. For the poem “In The Air,” I wanted there to be an unfoldment process, a story-telling, leading the reader, and the speaker, through the various emotions, sights and sounds. I use words like lines, trail, thread and the vertical form of the poem to try and do this—lead the reader through the experiences, to try and imagine what the Grandmother persona was going through, but also the speaker as well. What changes are these personas going through as the poem progresses, what happens to them, what is uncovered and learned? What are the themes threaded through the poem and threaded through our lives? What is in the space, in the air?

My first poem drafts are often handwritten in a notebook—actually there’s a whole process that goes on in my head way before that. Hardly any of my poetry writing comes straight from writing, it’s from a ton of thinking and a hell of a lot of reading. The writing part is often towards the end of the process. Actually, I spend most of my time in my head, so it looks like I’m not doing much ‘work’. So, after revisions in the notebook, when I feel happy that the poem content, themes etc., have reached a certain stableish stage, I then type it out in MS Word and work more on the aesthetic form, line breaks etc. So, anyway, one of the technical issues that came up when publishing Guabancex, was that there are strict rules as to the maximum number of pages a chapbook or pamphlet contains, and the poem “Hurricane PraXis (Xorcising Maria Xperience)”, actually started out being formatted quite differently when I first typed it out in MS Word. Due to the reduced page size of book, and the limited number of pages I had to work with, I had to change the original format, as I didn’t want to cut the poem.

So, I used tabs instead of line breaks for many lines and tried to use the form and spacing to further enhance some of the poem’s themes of dislocation, fragmentation of time and our physical space, disorder—and sometimes order, when the space distance is equal and the words line up.

I wanted the poem to feel overwhelming, to have a sense of relentlessness, a sense of ‘when is this going to end’, hence the use of repetition and the lines close together. But at the same time, it had to be a careful balance, as I didn’t want the reader to give up—there needed to be a bit of breathing room, and the spaces were there for that as well. Towards the end of the poem, you will see a lot more of the words line up, a feeling of more order returning and also there are a lot more spaces in the final lines and the use of indentation, which was to represent more breathing room but also things lost, missing, moved. The poem also transforms from a collective ‘we’ to an individual ‘I’ as well.

So, the visuals and words were trying to represent some things forever changed, fragmented, broken, missing—but also made whole—and some things whole and unchanged—but still fragmented, broken, missing. All of this trying to reflect the complex, incongruous, paradoxical time of disorder, chaos, loss, despair etc., but also a time of hope, order, routine, gratitude, grace, beauty and love.

I spend a lot of time thinking about space, and often a difficult thing for me are the stanza breaks. For some poems, I don’t want any stanza breaks at all, because I want to maintain that tension for the reader, and deliberately make them quite intense to read.

I also love concrete poetry and sometimes I get the sense it’s not always taken seriously in the literary world—I get that impression in certain circles it’s seen as gimmicky? I feel sometimes Jordan, poetry generally is taken so seriously and I actually like to play a lot in poetry. I wonder if we could have a different word for what we do besides our ‘work’, even terms like ‘workshop’. Although I take what I do seriously, I just feel that the fun element gets missed.

As I mentioned I love wordplay—I think in recent Kahini interviews, both Ellen Belieu and Kelli Russell Agodon talk about the wordplay aspect—that’s why I love reading interviews with writers, not only do I learn so much about aspects of the literary world and the craft, they can also give me confidence that I’m not alone in thinking or doing this or that.

JH: Like, “what are you playing on, these days!”

CS: Yeah. I would like to see that mentioned more. Sometimes I think there’s so much beating poets over the head…

JH: Oh, yeah.

CS:… all the time. And again, maybe it’s because I’m not from that tradition…

JH: Oh, no, no, no. It’s just as bad over here. Not to interrupt you but sometimes I feel it’s worse over here the craft focus is so intense that you’ll have these perfectly crafted little poems, but there’s no emotional engagement, at all. Like, it’s so well-done that it’s pointless. Or poets go the other way, deliberately, and it’s so much emotional abstraction that it falls apart like sand.

CS: Exactly. And I think that’s how I started because I thought that’s how I had to be, in order to be taken seriously. And I’ve kind of ditched a lot of that now, not the craft tools, but being too uptight and strict about it. I think you can be serious about what you do, but also have fun in the process. I don’t think those two things have to be mutually exclusive.

There’s so much pressure, especially on young writers, I feel. So many rules that they’re told they have to follow.

I hear so often, “You’re not a serious writer.” And I’m like, “What does that mean?”

Assuming someone is not serious could actually mean things like lack of access, lack of information, not having the finances to attend workshops, pay to do advertising, pay to buy journals, books etc or not having the luxuries of the time or a space to work. But I get it too, other writers in the same boat find a way through.

JH: Some of your poems are after Kwame Dawes or after W.S. Merwin. Who were the poets that you find yourself returning to over and over?

CS: I’m always a bit wary of that question, as I have a huge and diverse list of poets that are in my current reading and resonating space and it’s stressful to have to just pick out a few to name here, especially as I don’t hold them in any sort of hierarchy. Even if I started with my Caribbean family of writers, I’d want to list all of them. I will say though I’ve just finished reading the poetry collections by Richard Georges, which I loved, and looking through my notebooks, poems by Lucille Clifton, Tracy K Smith, Kwame Dawes and W.S. Merwin seem to appear the most. Also, when a poet’s writing resonates, I look at who they have been published by, and often it is Copper Canyon Press. But as I always say, my advice to anybody would be to pay close attention to which writers are in this space for you, what poems come to your attention, as opposed to who anyone else is reading or not.

Also, I’d like to say on that front, sometimes I find there seems to be a lot of snobbery in the literary world, in terms of the canon, and who should be read. I totally understand that there’s a rich tradition of poetry and poets, but the canon appears to be a particularly focused aspect of a western canon, and mostly limited to US and England. And I feel some of the do’s and don’ts that we get taught about poetry, are restricted to these perspectives and also stem from historic reasons that don’t always still apply.

It would be great to see the traditional poetry canon and the way poetry is taught, expand a lot more in terms of who and what is included and excluded.

I try to read poetry from a diverse spectrum of writers, from different cultures and regions, and often work resonates and moves that goes totally against the ‘rules’ I have seen and personally been taught.

I love to read poets that challenge, push, blur, or break the boundaries of any fixed notions about what a poem is supposed to be.

No Comments